Carlson Gracie, fighter

Carlson Gracie, fighterCarlson succeeds Helio and claims the 50s and 60s as his decades

By Luca Atalla, with Marcelo Dunlop and Rafael Quintanilha

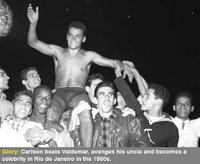

As people rolled over one another’s heads on a grandstand that had never been and would never again be that packed, Carlson Gracie avenges Helio’s defeat by punishing Valdemar with standing punches, strikes from the guard and elbow-blows from the mount. A massacre that lasts 39 minutes and 20 seconds, until the “Black Leopard” leaves the ring and his second, journalist Carlos Renato, throws in the towel.

The bout held July 21, 1956 was the second between Carlson and Valdemar. The first under mixed martial arts rules. Amidst so many glories attained in over 70 years of living, none compared to that day’s.

The story of the charismatic, perseverant and stubborn boy named Carlson begins in the district of Botafogo, Rio de Janeiro, on August 13 of 1932, ’33 or even ’35, as his passport states to this day. Maybe due to a confusion caused by an alteration made in order to make him take part in a tournament while still underage, age becomes a great charade in the life of the myth. You might try to guess it by looking at the picture of a self-defense demonstration performed with uncle Helio in the gymnasium of Brasil club, taken in 1937. In an interview given in the 50s, Carlson says he was 5 at the time. In more recent ones, however, predicting people might do the math, he claims to have been two and a half years old then.

Despite the talent shown in the move, Jiu-Jitsu was but a pastime in those days, he’d often admit. When mother Carmem died, he left Rio and moved with his father to Fortaleza, where he lived his childhood from age seven on. Back to Guanabara (nowadays Rio de Janeiro) state, at uncle Helio’s, at 82 Flamengo beach, ninth floor – well, then, already a teenager, he wore the gi, which for years he would only take off in order to sleep naked over a sheet spread on the mat. Or when, out of defiance, he decided, much to his father’s and uncle’s dismay, that he would fight m.m.a. without it on.

Whatever his exact age was, young Carlson was a born talent. Before he even had fully developed bones, he fought Japanese Sakai in a bout preliminary to Helio vs. Kimura, in 1951. The draw felt like a win to the 25kg lighter kid, 10kg under the 75,7 with which he would face Valdemar in 1956.

It’s unknown whether it was the fault of the quiet results that led him to being Rio’s champion in 1949. Or the ease he performed his daily academy errands with, where he was constantly challenged by “invitees.” Or even the disproportionate, uncommon strength for his weight, and the natural notion of distance. Most likely it was none of these factors, but actually the rebel temper usually found in groundbreaking artists. The fact is Carlson was undisciplined, and had to be followed closely in order to become a champion.

Brothers Helio and Carlos then acted. With a stern, harsh voice, Helio demanded military-like discipline in schedules and tasks. With his vision, Carlos motivated the son of the director of the Deaf and Mute Institute, in Laranjeiras, into training hard. Joao Alberto Barreto would be, for years, Carlson’s stimulus. Not so much in trainings (where that rivalry took a backseat), but at the furthermost post at the battlefield.

So much that, several times, including in the great victory mentioned above, Barreto was offered as an alternative to Carlson. “There was no sense in me fighting Valdemar. It was something someone in the family had to settle. But as soon as Carlos mentioned me as a possibility, Carlson started training,” Joao recalls, clearing up the reason why his name was on the headlines of “O Globo,” “Ultima Hora,” “O Dia,” and “Jornal dos Sports” the day before each fight.

Debut for the unfornate

Up until Valdemar defeated Helio, the “Kiddo,” as Carlson was called, occupied only secondary spots in the newspapers’ stories. He had, of course, faced Jiu-Jitsu challenges and at least three mixed martial arts bouts. In the premiere, against capoeira practitioner Luiz “Cirandinha” Aguiar, he raised 38 thousand cruzeiros for the people who had suffered with the drought in Northeastern Brazil. In this March 17, 1953 bout he spent over one hour to win, “because, at the request of my father and uncle, I couldn’t use any Jiu-Jitsu moves,” he told the press. Tired of getting hit so much on the cement of the basketball court of Vasco da Gama club, Cirandinha gave in.

The second m.m.a. bout, against Wilson Oliveira, a.k.a. “Passarito,” in May 1953, had also the excuse of giving the audience’s money to the victims of the Northeastern drought. It was held on a canvas on the field of Maracana stadium and, in spite of lasting a few minutes less than the previous fight, was much more difficult. It ended in a draw – and Carlson, again, took off the upper gi during the combat.

Carlson wouldn’t need to bear the memory of the draw for long. Almost a year later, in March 1954, there was a rematch. In the longest fight of his career, Carlson punished the opponent in the fifth 30-minute round, and forced the capitulation of this 98kg athlete who practiced wrestling, boxing and Jiu-Jitsu, having been a pupil of master Carneiro.

In between seasons in Teresopolis, where he’d paint all of the cicadas white, and endless weeks in Rio teaching Jiu-Jitsu, which he’d interrupt to the sound of any aircraft and, without glancing, would guess the prefix of the plane that was going up from Santos Dumont airport, Carlson left behind the first half of the 1950s. And no matter how thicker his ear got, maturity didn’t seem to be any nearer.

Passers-by in suits could very well notice this, for they would often be surprise by the buckets of water falling onto them from the 17th floor of 151 Rio Branco Av. (the city’s financial center).

Carlson didn’t follow his studies since he left the state of Ceara. But his keen brain didn’t only store an amazing amount of fight moves. It was also able to memorize a nearly entire dictionary, entry by entry. Or learn all of the lyrics of his bolero LP collection.

The star is born

Then came the challenge by former training partner Valdemar Santana to Helio Gracie, in May 1955. The fight, not entirely a business-only matter, happened, with no entrance fee, at Rio’s Young Men’s Christian Association, for nearly four hours. And Valdemar’s victory made Carlson a star among Gracies. Not that Helio was no longer a tremendous champion. But it was obvious that, aged 42 and weighing no more than 63kilo, he was no longer the most indicated soldier in the family for such a battle. It was Kiddo’s turn.

Stadiums were packed to watch the duels between Carlson and Valdemar. There was a total of four in five years. The first, a Jiu-Jitsu match, in October 1955, ended in draw (at the most critical moment, Valdemar’s tactic of jumping out of the ring saved him from a dangerous choke). The other three were m.m.a. bouts. There were no jurors, and Carlson won that of 1956. But he had a clear advantage in the one held in 1957, where he was unable only to make true his public promise: that of finishing the fight early in order to go home listen to his brand new bolero records. The Leopard himself admitted before their most balanced fight, the 1959 draw: “It is true my blood has already dyed the canvas of Maracanazinho gymnasium.”

Carlso became a celebrity. Soon there were easy passions, many friends, and a great throng of people accompanying him wherever he went, especially the 1950s’ Copacabana. Money, he got nearly none from the fights, and whatever he did get, he’d spend right away. But, after all, what does one need money for with all that fame?

Even with a child’s temper, Carlson wound up making a mature decision: a beautiful blonde called Yone caught him good, and they got bound in wedlock. From the fleeting union came Rosangela. This was the biggest news in the early 1960s.

End of a stage

Fighting was a good excuse not to spend the day teaching. And thus Carlson beat, at America club, the enormous King Kong, whose overwhelming size once made the police’s job quite tough. Mixed up in a brawl, he couldn’t be arrested, for no pair of handcuffs fit him. And, before his hardest fight ever, he packed Maracanazinho so that people could get a look at him mounting on Karadagean.

The fight in Recife, Pernambuco, in December 1963, didn’t demand so much practice. After all, a man 1,73m tall and 98kg heavy “can only be a chubby fellow,” the Kiddo reckoned. This impression only lasted till Paraiba’s Ivan Gomes got into the ring and took off his robe. “He was all muscle, there was no fat at all. And, as he had trained Jiu-Jitsu with a pupil of uncle George, he had technique as well,” the grandmaster analyzed over 35 years later. Those were the hardest 30 minutes he ever went through in combat, Carlson would away say. In the end, a tie. Gomes, according to Gracie, spent days in hospital, with a broken face and a black leg. Carlson, according to friends, was hit on the face for the first time. He got to the airport in Rio wearing sunglasses. His eye had swollen.

Carlson then went to Salvador, Bahia, to suffer the only loss on his record, against Euclides Pereira. It was a defeat disputed by Gracie till the very end: “I even arrived at a rear-naked choke, but he escaped the ring. The jurors were the only ones who thought I had lost,” he’d say, always with a complaining tone of voice. But if the loss hadn’t been that evident, the lack of stimulus for training that hard was. And uncle Helio, busy with the upbringing of his own children (Rorion, Relson and Rickson) and of nephew Rolls, no longer demanded so much from Carlos’s first born. Little after his 30th birthday, it was now time for Carlson to quit being the Kiddo.

___

This is only part of GRACIE Magazine #109, a historical issue published in honor of the grandmaster, featuring 43 exclusive pictures. The other parts ("The tutor," "The wound," "The immortal" and "Carlson, by himself") will be published here in the course of the following weeks. The complete issue, in Portuguese, can be purchased at graciemagshop.com.

.jpg)

1 comment:

...nice blog

Post a Comment